16.12.2016 00:00:00 - 29.01.2017

Uroš Đurić:

An Infamous Collapse Of The Class Struggle

& Other Tales For Defeated Society

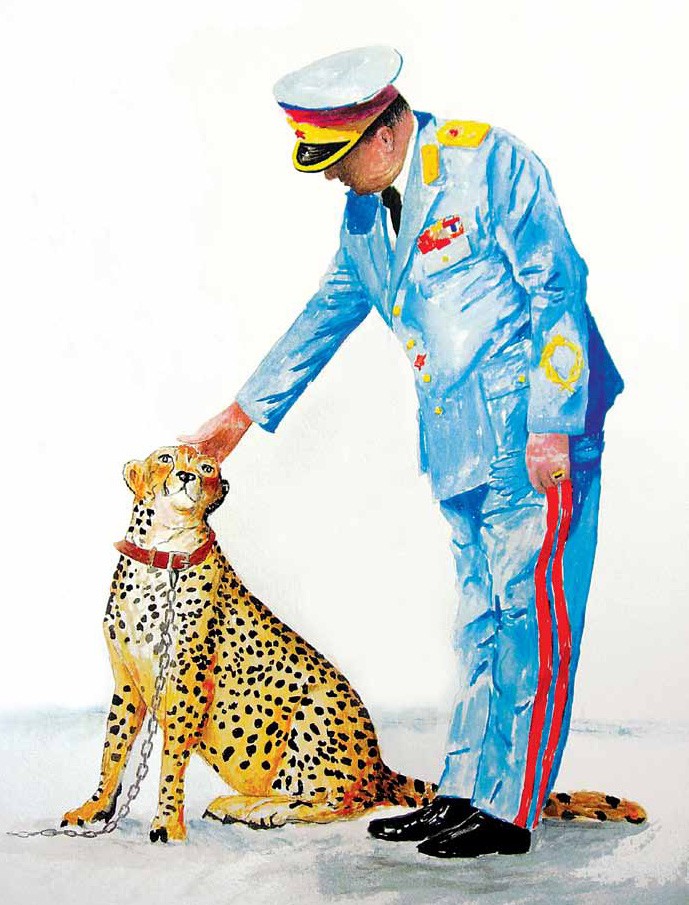

Fiction and specific events, real and imaginary characters or objects, historical styles and trends, ideas, signs, symbols and images in paintings and drawings of Uroš Đurić, entrancing Serbian artist, representantive of "autonomy" movement.

The personality of Uroš Djurić has been causing confusion, debate, doubt and controversies ever since his emergence on the Serbian art scene. The symbolic act of his stepping through the so-called grand entrance of the art scene could, however, be marked by the beginning of joint exhibitions with Stevan Markuš, in 1989. The theoretical articulation of joint artistic activity followed in March 1994, when Djurić and Markuš signed and published Manifest Autonomizma / Autonomism Manifesto together. in a country which was rapidly disintegrating and falling apart at the seams- where the war machine, as well as social and economic poverty crushed everything in sight, forcing collectivization and uniformity as desirable values, Djurić and Markuš were declaring autonomism to be the supreme principle of their art. The submission exclusively to their own laws and personal (personalized) principles renders this two-member movement an incident, that is, an energy which, according to many theorists, critically marks the situation of the return of figurative painting in the 1990s:

There is a need for an establishment of a possible reality, separate both from the real world as from art itself, in which fiction and specific events, real and imaginary characters or objects, historical styles and trends, ideas, signs, symbols and images would be functioning smoothly. (Uroš Đurić, Stevan Markuš, Manifest Autonomizma / Autonomism Manifesto, Contemporary art Gallery of the Cultural Center “olga Petrov”, Pančevo, June 1995.)

Djurić and Markuš thus define their parallel visual realities at a time when all of Serbia is living in constructed parallel realities in which turbo-folk, kitsch, populism and social escapism of all kinds are becoming dominant values. Playing with contexts, the autonomists confront the parallel realities of Serbia of the suburbs and the culture of tracksuits, with the modernist tendency towards the aestheticization of society, renegade culture, leather jackets, historical avant-gardes and the authentic Belgrade urban spirit. Self-proclaiming themselves as living classics, as well as the greatest Serbian painters (see Djurić’s programmatic paintings: Dva najveća srpska slikara u brišućem letu/ Two Greatest Serbian painters in Looping, 1990, Bespredmetni autonomizam: Ubistvo ili dva najveća srpska slikara umirena svojom veličinom/ Non-objective Autonomism: Murder or Two Greatest Serbian Painters Subdued by Their Own Eminence, 1997), the autonomists deliberately provoke, and also irritate the art environment which, with its own cocooned outlook, certainly could not remain immune to such excesses. The manifesto was intentionally implemented as a slap in the face to social taste, and also the art scene, itself, since, according to the authors, the immediate reason for its conception was actually an attempt at minimizing vacuous conversations about their art. Instead of a position of an artist who depends on the context in which his art is being positioned by curators, gallery owners and other actors of the (non/existing) art system - autonomists construct their own artistic context (contexts): The beauty of this painting is also in a charming, but determined rejection of artistic mystifications of the work itself, and the ironic approach to the concept of culture and its contemporary and/or historical layers makes Djurić’s work an excellent representative of what we might call “fictional site” or “active escapism.” (Lidija Merenik, No Wave: 1992–1995, in: Art in Yugoslavia 1992–1995, Fund for an open society, Center for Contemporary art, Belgrade, 1996.)

Djurić has held onto thus marked autonomist positions from the moment he began to exhibit independently, replacing classical painting techniques with various experiments in the field of expanded artistic media. What remains unchanged is the presence of the author’s image - namely, the self-portrait as the thematic thread that connects various phases and series of Djurić’s complex artistic opus. The second (variable) constant are urban values that autonomists also promote within the informal arts community Urbazona - a project initiated in the summer of 1993 by another cult figure of the Belgrade countercultural scene, the painter and radio presenter Miomir Grujić Fleka. With the support of the independent radio B92, it was Urbazona that was trying to legitimize and make visible one of those principles which remains dominant in Djurić’s art until the present day. This principle, briefly, could be summed up in an attitude that the artist is a person engaged in the defense of the city. The artist is responsible for the city in which he lives in. For its spirit. Urbanity. He is the one who differs and who constantly points out differences, he is the one whose language and energetic charge are difficult to fit into the narrow, intolerant and in every way tragicomic system of cultural values. (Miomir Grujić, Uputstvo za prijem i dalje emitovanje, katalog za Akciju No.5/ Instructions for Reception and Further Broadcast, Action No.5 Catalog, Urbazona, Belgrade, 1993.) along with Jugoslovenska kinoteka, Klub akademija, cinema rex, gallery sebastian, and Paviljon Veljković had all become cult places of Belgrade’s urban scene in the 1990s, as did the Belgrade streets and private apartments.