07.02.2008 18:00:00

INVISIBLE PARLIAMENT

(with Lukáš Jasanský and Martin Polák)

Text by Ivan Mecl

At the beginning of the 1990s, philosopher Mirek Vodrážka indicated in his Lao Tse-inspired texts that the best government is that which citizens do not even know exists. It’s possible that he didn’t realize then how close his prophecies were to becoming true. The European Parliament is truly something about which we know nothing. I only know a couple of people who have seen it from the inside. But I’m almost certain that you could dupe most people into believing that deputies meet in the Brussels catacombs and the building above ground is just a large parking lot.

What is good? What is bad? No one knows. Perhaps only the person that creates them, as Nietzsche opined. Perhaps they know what they are doing in Brussels. But all that we learn about their work is misinformation. This does not mean that there is some premeditated, distortion-focused media campaign going on. The best misinformation is that which need not be created or invented. It comes from journalists’ disinterest in trying to tackle a complicated issue and the inability to understand the special coding of messages into pro-European newspeak: very long messages.

Recently a group of photographers, perhaps inadvertently, revealed that the European Parliament is often almost completely empty, and the rest is just a Potemkin Village. Non-existent institutions or institutions that create only virtual activities are one of democracy’s greatest gifts. These activities do not impact or affect anyone, and so these institutions are beloved. The European Parliament is a literal personification of the European Union, because each country has its representative there and so everyone likes it. Just look at how our top political representatives happily return from meetings in the European central offices. Even though they do not speak foreign languages, they proclaim how they negotiated top-level agreements with foreign delegations, all of which are advantageous for our country. Only a crazy person would believe them. But until things get worse, they will continue to pat one another on the back.

But let’s go back to the awful truth that was revealed about the European Parliament. The Goethe Institute and a team of pleasant, confused gallery operators, Thomas Huber and Jörg Koopman, invited a number of artist-photographers to Brussels to show what it’s all about, this European Parliament. Hopefully the criteria for selecting the photographers will remain secret for posterity. I sense however that the organizers approached gallery owners, who later chose from among the least-used artists in their employment. So far the work has only been shown on the premises of the aforementioned parliament. So almost no one knows about the project. I became interested in it after overhearing Lukáš Jasanský and Martin Polák—a pair of sarcastic artists who could easily set up a TV channel to amuse even the most disenchanted and skeptical of intellectuals. It would broadcast in black-and-white, full of technical difficulties, with the two of them at the helm, having the most fun of all. What follows are a few excerpts from an interview with the pair.

Most of the photos show only interiors? Why?

When we arrived we were told that we could only photograph inside. Apparently the building’s architect has licensing rights for photographs of the building. He has the right to approve all photos. One photographer was not discouraged by this fact. He photographed the building’s exterior, but from such a distance and in such a composition that it failed to occupy even half of the space in the picture.

That’s strange. It’s not possible to set such limitations, is it?

Hard to say. The building is too ugly and too big. Plus it can be seen from all over. Perhaps the architect doesn’t want people to find that out. Thus he only allows pictures to be taken from certain, acceptable angles. Otherwise, the building definitely suits that which it is meant to represent.

There are no people in your pictures. This happens often in your work. But pictures by the other artists also lack people. And in the photos where there are people, they all seem arranged somehow.

Because the parliament is almost always moving, it is often empty. The deputies get up and leave, their assistants pack their bags and load them into trucks to be carted off to Strasbourg or Luxemburg. We were all there at a time when no one was home aside from the maintenance staff and a few employees. In fact there was really nothing at all to photograph. There’s almost nothing inside, and what is there looks like elements from any other administrative building—just bigger. Some photographers did actually arrange people. But the movement of people there is excessively civil, gray. This is also impacted by the extremely mundane setting of Brussels. One photographer sort of exaggerated his work and put people in various tragi-comic positions.

Isn’t it just a fictitious institution then? Just a big facade?

They’re always working on the building: fixing or re-doing something. Technicians are laying cables, they’re opening soffits and drilling into the walls and ceilings. The place is filled with long hallways and conference rooms of all sizes. Numerous offices, dark ones and lit ones. Spaces with tons of unused technical equipment. An abandoned TV studio, poised and ready for a broadcast. We never saw it up and running. There is so much equipment that never gets used. And the people work to keep it all on “stand-by,” visually at least. We’re not sure if it actually functions.

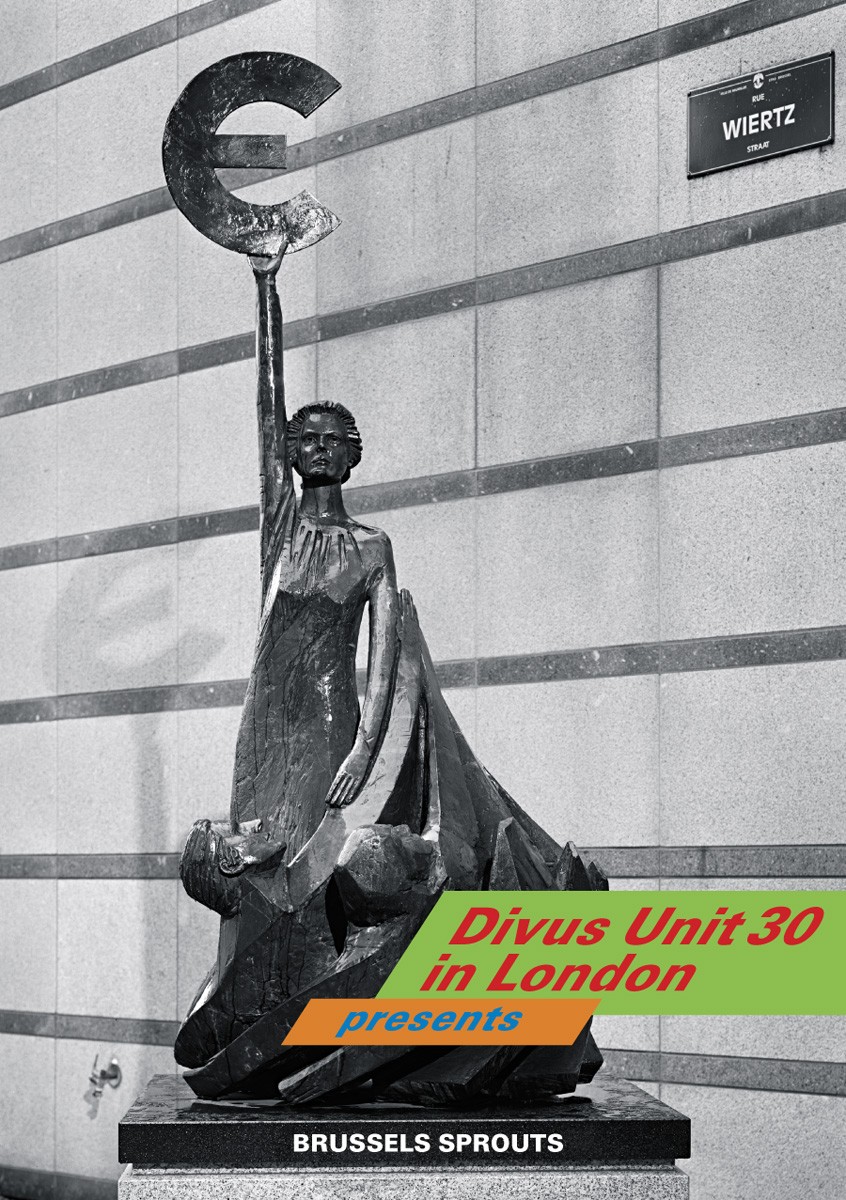

So ultimately you decided to photograph art.

That was the most abandoned stuff that we found. As we wandered around the building and into its’ various corners we began to discover artwork in the least likely of places. There was a strange variety of styles and forms from engaged, pro-European statues and reliefs to horrid samples of the international informal style. We figured out that art is what binds Europe together…bad art. Bad art is the same everywhere. Perhaps this is why it’s represented in the Parliament. So we decided to photograph it.

So how did the gallery operators and Institute like the results of your work?

We think that they didn’t like it much. It took them a long time and much effort to assess our photos. They didn’t invite us to the exhibit. But they did send us the catalogue.

The catalogue was surprisingly the biggest contribution to the exhibit; mainly because it contains a wonderful essay by an editor from Germany’s Tagesspiegel, Robert Birnbaum. He used it, among other things, to develop his own universal parliamentary theory:

“Democracy in practice is the most highly abstract and incomprehensible type of government. Whoever does not believe this should take a test. First, envision some type of castle and imagine how, in his day, King Ottokar der Heizbare ruled there. It’s not that difficult, is it? A king, a couple of advisors, perhaps some éminence grise in the background – the personnel and decision-making structures in a monarchy are transparent. Afterwards he accompanies a normal group of visitors to see the Reichstag in Berlin, the Sejm in Warsaw, the Cortes Generales in Madrid, etc. Prior to the tours, the visitors' faces were lit with looks of happy expectation – afterward expressions of mild confusion.

Most definitely they saw the assembly room with the speaker’s podium up front. But to find an answer to the question why, for example, the Berlin Reichstag in time of debate is almost completely empty, is in itself complicated. It relates to the number of weeks in plenary and the legislative documents, to the difference between a debate and a working parliament, to the residential care of the deputies, only to name a few of the reasons. All by itself this seemingly simple question leads deep into the institutional underbrush of the Parliament that only political enthusiasts or hobbyists care to follow. All others continue to be satisfied privately with the suspicion that the explanations are invented, and the deputies are lazy.”

However in the end even the journalist gets frightened by his criticisms and in his final words decides to give the European Parliament a chance, both as an artifact and a thing of curiosity. I began my correspondence with the project organizers by asking how much they thought the artists suffered working on such a silly project. I was answered with a yell: “But who can appreciate our suffering?” There, there. It’s not without good reason that we say “Don’t take your lord out onto the ice, Vasek. Your lord will fall and you will break your nose.” Goethe Institute please bear in mind this oft-repeated fact: no one knows anything about the European Parliament. They wanted to show in artistic photos the work of the “only directly-elected EU body.” But the question remains whether the Germans wanted to ingratiate or take revenge on the Parliament (an empty mass). Artists can stand on their head trying to extract some meaning from the Parliament. Institutions are not responsible for their own failure. We can only hope that the conspiracy was only the project of the Goethe Institute and that the level of opportunism on the part of the project organizers was minimal. The results can be presented as an example of an office joke.